Soviet Treblinka Investigation 1944-September: Difference between revisions

| Line 896: | Line 896: | ||

Question: Name the camp staff members responsible for all the atrocities committed in the camp. | Question: Name the camp staff members responsible for all the atrocities committed in the camp. | ||

Answer: Of the individuals responsible for all the atrocities committed in the camp, I remember the following:# Unterschaftführer Schwarz – a German about 40 years old, tall, black-haired, black-eyed, and thin. He personally beat women and shot men. | Answer: Of the individuals responsible for all the atrocities committed in the camp, I remember the following: | ||

# Unterschaftführer Schwarz – a German about 40 years old, tall, black-haired, black-eyed, and thin. He personally beat women and shot men. | |||

# Workshop Supervisor Unterschaftführer Stumpe – a German about 30 years old, tall, black-haired, and dark-skinned. He personally beat women. He supervised the work teams and assigned workers. | # Workshop Supervisor Unterschaftführer Stumpe – a German about 30 years old, tall, black-haired, and dark-skinned. He personally beat women. He supervised the work teams and assigned workers. | ||

# Unterschaftführer Reger – about 25 years old, short, fat, blond, round-faced, and red-faced. He was the head of the guards. | # Unterschaftführer Reger – about 25 years old, short, fat, blond, round-faced, and red-faced. He was the head of the guards. | ||

Revision as of 06:25, 17 December 2025

In September 1944, a joint Polish-Soviet group of investigatory bodies conducted an examination of the area of the Treblinka camps.

Members of the Polish-Soviet Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes, the Information and Propaganda Department of the Polish Committee of National Liberation, and the Military Council of the 2nd Belorussian Front were involved in the investiation.

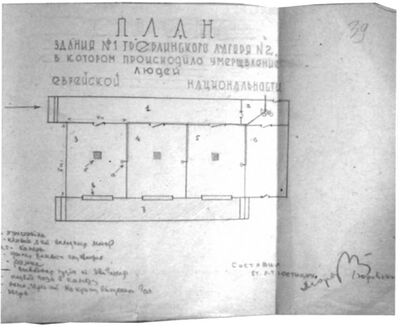

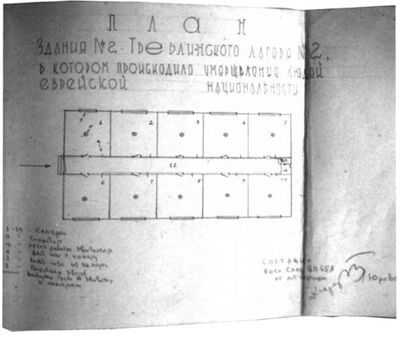

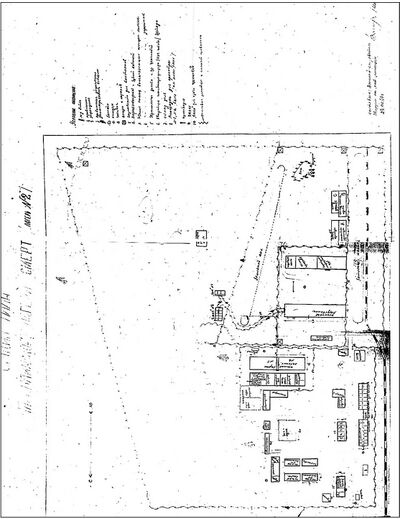

The documents below include interrogation protocols of witnesses, a map of the Treblinka II camp, schematics of the gas chambers, and the official report.

Report from the correspondent of the army newspaper “For the Motherland” Major D.I. Novoplyansky to the head of the political department of the 70th Army Colonel Maslovsky, September 9, 1944 (certified copy dated September 22, 1944)

While fulfilling the editorial assignment, I twice visited the site of the Treblinka Tod camp (death camp), established by the Germans between Warsaw and Białystok (6 km south of the Małkinia Górna junction station).[1]

Former prisoners Wolf Szejnberg and Mendel Koritnicki, who previously lived in Warsaw, speak about this in more detail than others.[2]

It's clear from the accounts that in July 1942, the Germans ordered all British and Americans to assemble at Warsaw's Prison Square for an exchange. Notices were posted stating that the Germans had reached an agreement with the Allies to exchange British and American prisoners for German prisoners of war. It was also strongly emphasized that for every British or American, the Allies would give up two Germans. The British and Americans were GUARANTEED TO RETURN TO THEIR HOMELAND. Wolf Szejnberg personally read such an announcement. The existence of such announcements is confirmed by former Warsaw residents Szymon Cegiel, Eney Tracz, and Korytnicki, who currently reside in Kosów (Węgrów County).

Szejnberg and Koritnicki testify that British and American citizens, along with their families, were transported from Warsaw to Treblinka in trucks in July 1942. People in the city knew that foreigners were being taken to Treblinka, but at the time, the name meant nothing to people. Some simply expressed surprise: after all, Jews were supposedly being taken to Treblinka for work, so why were British and Americans being taken there for exchange?

Wolf Szejnberg, who was lucky enough to escape death and later worked as a baker in the Treblinka camp, claims that the British and Americans were not held in the camp for a single day, but were, along with thousands of others arriving at Treblinka, immediately sent to the "bathhouse," where they were killed. He knows this from a number of conversations in the camp, including those of the German administration. Unterscharführer Schwarz, for example, said that the British bombed his home and family in Lübeck, for which he took revenge by participating in the extermination of the British there.

Wolf Szejnberg currently resides in the Albinów estate (4 km northwest of Kosów). He is also connected to several other witnesses living in Węgrów, Kosów, and Sokołów Podlaski.

Koritnicki, who arrived at the camp somewhat later and subsequently worked as a tinsmith at Treblinka Camp No. 2, personally saw suitcases belonging to Americans and British prisoners near the "bathhouse," among the belongings of the murdered. He asked who these seemingly unusual items belonged to, and several people explained that the British and Americans had "passed" there and that these were their suitcases and other belongings.

Considering that the question of the extermination of the British and Americans in the Treblinka death camp is of exceptional political interest at the present time, I request your petition to appoint an investigation into this matter.

September 9, 1944

MAJOR Novoplyansky

Protocol of the preliminary investigation and information about the former concentration camp Treblinka, September 15, 1944.

According to the instructions of the Chairman of the Polish-Soviet Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes, Mr. WITOLD A.,[3] the Secretary of the Polish-Soviet Commission, Mr. SOBOLEWSKI P.,[4] the representative of the Information and Propaganda Department of the Polish Committee of National Liberation, Mr. HODŹKO,[5] and the representative of the Military Council of the 2nd Belorussian Front, Lieutenant Colonel LEVAKOV G. E.,[6] visited the site of the former concentration camp in Treblinka, created by the German invaders for the mass extermination of citizens of Poland and other European countries.

The Treblinka[7] area is located 7 kilometers from the Małkinia railway junction in Sokołów County. German bandits built a railway line directly to the camp site to transport prisoners directly and undetected to the concentration camp.

The camp is located in a forest, one kilometer from the highway and the railway line leading from Małkinia to Siedlce. The concentration camp is surrounded by three rows of barbed wire and anti-tank forts.

The remains of burned-out barracks, the charred walls of brick and concrete outbuildings, and a large number of scattered household items were discovered: bowls, mugs, forks, children's toys, scraps of documents and books, torn pieces of clothing, and numerous shoes of all sizes and types. The earth was dug up, and the smell of decomposing corpses was palpable. All of this indicates that this is where German murderers carried out mass exterminations using their well-known "scientific" method.

Under the onslaught of the victorious Red Army, the German murderers, trying to erase the traces of their crime, burned and destroyed everything they had created at Treblinka during the three and a half years of the concentration camp's existence.

The forest clearing where the camp is located is a sandy field overgrown with small trees and surrounded by a dense pine forest. This forest shielded the concentration camp from view.

According to the testimony of former camp prisoner Jacob DOMB,[8] a resident of Warsaw, Franciszkańska Street, 24, DAWYDOWSKI Jan,[9] a resident of the village of Poniatowo,[10] a former prisoner in this camp, Maria WLADARSKA, a resident of the village of Grondy, 2 kilometers from the camp, whose husband died in Treblinka, and KORITNICKI, a resident of the fort of Albinów,[11] located near Treblinka, IT IS ESTABLISHED:

The Tremblinka concentration camp was divided into two parts, located one and a half kilometers apart.

The first section was called "Death Camp No. 2." This camp, on the site of which two burnt-out outbuildings now stand, was also divided into two sections, with a railway line leading to Camp No. 2. Something resembling a train station was built here to conceal the primary extermination mission. A triple wall of barbed wire was concealed by tree branches. Therefore, those brought here initially believed they were at a transfer point heading east.

In the first section of Death Camp No. 2, the arriving prisoners were stripped. Their clothes were ordered to be placed in a designated area, and then, naked, they were forced to run with their hands raised toward the so-called bathhouse. The bathhouse was disguised as a public bathhouse, but in reality, it was a three-room gas chamber. Initially, they resorted to sucking the air out of the chamber using a small car engine. Later, due to the large number of people being brought to their deaths, chemical agents were used. This chamber could simultaneously house and kill approximately 400 people. On the roof of this hermetically sealed chamber, there was a small window for observing the death throes of the dying. Women had their hair cut before being strangled, and their hair still lies at the scene of the crime. About 400 Jews worked in this chamber, carrying the bodies of the strangled to large pits dug by moles, which were previously prepared and located within Death Camp No. 2.

In the winter of 1943, German murderers began digging up and burning corpses. They also used shrews for this purpose. Torn fragments of personal documents found scattered here prove that citizens of Poland, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and other intellectuals, as well as ordinary workers, were murdered here.[12]

The second part of the concentration camp was called "Camp No. 1" and was located one and a half kilometers from the death camp. Camp No. 1 was similarly fenced with a triple row of barbed wire and anti-tank forks. This part of Camp No. 1 was divided into four fields,[13] the first field containing eight barracks and housing the commandant's office and guards, consisting of approximately 200 SS men and their assistants. This field also housed food storage facilities, outbuildings for horses and cattle, buildings for chickens and ducks, garages, a local power station, and even a small swimming pool for ducks. From here, a road led into the forest to the executions.

The second part of Camp No. 1 consisted of three fields, with one barrack each built in the first and second fields, and two barracks in the third field. Women were imprisoned here. Each barrack was separated from the next by a high wall of barbed wire.[14] This part of Camp No. 1 housed the kitchen and workshops—a metalworking shop, a carpentry shop, a forge, a weaving bench, and an engine. A large concrete cellar still holds the remaining potato reserves.

The total number of prisoners was approximately 3,000 per day. Twice a day, the so-called "appel," or inspection, took place, at which everyone without exception—the healthy, the sick, and the dead—was required to report. The sick were separated and finished off with sticks; some were shot. The dead were carried out by healthy prisoners. As a daily routine, the German criminals practiced beating prisoners, primarily on the head with a stick. Anyone incapable of work was also finished off in the same manner.

500 meters from Camp No. 1 lies a pine forest, and long mass graves begin at the edge of this forest.

According to the testimony of Jan DAWYDOWSKI, a resident of the village of Poniatowo and a former prisoner at this camp, these graves were dug in advance, reaching 4 meters deep, 6 meters wide, and approximately 300 meters long.

Executions took place over these pre-prepared pits, and people were finished off with a stick to the head.

DAWYDOWSKI personally witnessed German SS men bringing in entire carloads of people and then murdering them. He also witnessed an incident where they brought in three people, ordered them to kneel, and then shot them in the back of the head.

The freshly dug sand, the large number of human bones scattered everywhere, and even a severed foot lying in one spot, are still visible.

According to witnesses and prisoners, almost no one ever left Camp No. 1. The minimal rations led to rapid depletion of prisoners, making them unable to work, and ultimately, to their murder.

Witness Stanisław KRYM,[15] a resident of Tremblinka, whose home is 500 meters from Camp No. 1, saw vehicles transporting people to the forest. Some walked, and then machine gunfire could be heard: "I personally saw prisoners working at grinding stone and being beaten with sticks when they were too exhausted to continue. There were Poles and Jews here, as well as women and children aged 10 and older."

Witness Maria WLADARSKI,[16] a resident of the village of Grądy, located two kilometers from the camp, recounts: "I saw entire freight cars filled with people, heard screams and pleas for help. From our field, I could clearly see mountains of clothing where the prisoners who had been brought in would climb, undress there, and then descend and disappear somewhere. I heard the screams and cries of the dying, as well as music and singing—first from men, women, and children, whom the SS forced to sing before their deaths."

“My husband, Tadeusz Wladarski, died in this camp along with 40 other Polish prisoners within a few hours.”

Considering that the construction of the concentration camp in Tremblinka dates back to 1941, the area occupied by the camp is 5 square kilometers, its structure and facilities, the number of barracks, the existence of the so-called "bathhouse" - a gas chamber, the enormous quantity of things, the size of the pits – all this proves that hundreds of thousands[17] of innocent people were brutally murdered here, whose only crime was that they lived and that they did not carry out the orders of the German authorities on the delivery of food on time, carried on prohibited trade or did not remove the required amount of timber on time.

The items found indicate that men, women, and children of all ages, along with entire families, were imprisoned here. Items found, such as violin parts, children's toys, hair curlers, books, and other paraphernalia, prove that many arrived here unaware of their purpose.

Fragments of burned and destroyed passports prove that citizens of Poland, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and other German-occupied countries were imprisoned here.[18]

Considering that the Tremblinka concentration camp was one of the largest camps for the mass extermination of innocent people, it is essential to first collect all possible items from the camp grounds, especially documents, and hand them over to the Polish-Soviet Commission for investigation.

Preserve and ensure the protection of the camp site itself as an international memorial to the terrible tragedy that was endured.

In the near future, it is necessary to begin excavating the mass graves, which will reveal yet another secret of German crimes to the world.

Secretary of the Polish-Soviet Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes /signature/ (magistrate P. Sobolevsky)

Representative of the Information and Propaganda Department of the Polish-Soviet Communist Party of Poland /signature/ (M. Khodzko)

Representative of the Military Council of the 2nd Belorussian Front /signature/ (Lieutenant Colonel G. E. Levakov)

September 15, 1944

Treblinka

Interrogation protocol of Cheni Trać about the situation of Jews in the Treblinka labor camp and the mass shooting on July 23, 1944. The village of Kosów Lacki, September 21, 1944.

On September 21, 1944, the military investigator of the military prosecutor's office of the 65th Army, Guards Senior Lieutenant of Justice Malov, in compliance with Articles 162-168 of the Criminal Procedure Code of the RSFSR, interrogated as a witness:

- Last name, first name, patronymic: Cheni Yankelevna Trać

- Year of birth: 1913

- Place of birth: Zarlib-Kostlin, Ostrów Mazowiecka County, Łomża Voivodeship

- Nationality: Jewish

- Social background and status: housewife. Husband is a shoemaker from the working class.

- Education: 7th grade

- Place of residence: Kosów Lacki

I have been warned of liability for giving false testimony under Article 95 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR.

The interrogation was conducted through an interpreter, Burstein Heim, a resident of Kosów, Warsaw Voivodeship, who has been warned of liability for false translation. [Signature/]

In March 1942, SS soldiers arrived in Kosów from a camp located 8 km from Kosów. Along with the soldiers, the camp's leaders arrived: Hautsturmführer von Eupen, Untersturmführers Preif and Lanz, Rottenführer Mobis, and Navigator Felden, who had with them a list of the best Jewish artisans in Kosów. My husband, Trać Lejba, was also on this list as a good shoemaker. All the Jews on the list were herded into the town square and then driven under guard to the camp, which was called the "Treblinka Labor Camp." My husband remained in the camp until July 1944. During his stay in the camp, I met with him several times. When I met my husband, he told me about the terrible atrocities committed by the Germans and guards against the camp prisoners. The work was extremely hard—they forced them to dig the earth and uproot tree stumps. They were fed very poorly, causing them to quickly lose strength and productivity. If a prisoner couldn't work or worked poorly, they were brutally killed. Moreover, they killed in a painful manner, forcing the victim to suffer before death. The most common method of murder was a hammer blow to the bridge of the nose or head, followed by beatings with sticks and whips. Ten to twelve people were killed this way daily, not counting those who died of exhaustion and disease. A guard's stick or whip accompanied the prisoner everywhere. Horrific beatings followed at every step, beatings carried out without provocation—just for fun. They beat with whatever came to hand—sticks, shovels, axes, and even slashed with knives. I remember particularly well an incident that occurred in July 1942. When my husband saw his children at a meeting, he burst into tears, saying that "soon they will kill them like that too," and at the same time he told about the terrible picture of the extermination in the camp of 120 innocent children brought from Warsaw in July 1942.

As my husband recounted, children of various ages were brought to the camp, lined up in front of all the prisoners, and forced to sing songs. Then, out of a total of 120 children, 60 of the weakest and smallest were selected and taken to pits in the forest, where they were brutally murdered. The children were killed with sticks, whips, axes, daggers, and hammer blows to the face or head.

The heartbreaking cries of small children echoed throughout the camp. The 60 healthy children who remained in the camp subsequently died of exhaustion or overwork, or were murdered in similarly brutal ways. I witnessed all these atrocities and murders committed in the camp myself when I arrived there. This happened under the following circumstances. In March 1943, the Germans conducted several roundups and rounded up all the Jews living in the vicinity of the camp—women and children. They took me along with two children: my daughter Zosya, 13, and my son Abram, 8. All the women and children were placed in a separate barracks, separate from the men. There were 35 of us in the barracks. Upon arrival at the camp, we were forced to wash the laundry of the camp staff. The work was very hard, and the food was very poor. They gave us only 200 grams of bread a day, bad coffee in the morning, and beetroot or rutabaga soup in the afternoon. Cooked earthworms and other garbage were often found in the soup. Being near the men's work, I often saw prisoners being beaten with sticks, shovels, and other blunt objects. The usual method of execution with a hammer was to force the prisoner to lower his head, and when he did, they struck him on the back of the head with the hammer, which resulted in death. Sometimes they struck several times before finally killing the victim. When the Russian troops successfully advanced, we women and children were transferred to the men's camp for fear of escape, who were under stricter guard than the women. And here I saw the horrific extermination of the Jews more closely.

All the male prisoners were extremely emaciated and weak; the work was extremely hard: they dug the earth, sawed timber, and uprooted stumps. Food was limited to water in the morning and evening, and for lunch, soup made from beets or unpeeled potatoes, which contained a lot of sand and various debris. Guards walked everywhere with sticks and whips in their hands, beating every prisoner they encountered. Due to the backbreaking labor and terrible food, people quickly weakened and were unable to work, and such prisoners were killed with sticks, hammers, etc. Up to 10-12 people were killed in this way daily. I remained in the Treblinka labor camp until July 23, 1944. When the Red Army began to approach Treblinka, the Germans decided to exterminate all the Jews – men, women and children – who were in the labor camp, for which purpose on the morning of July 23, 1944, they herded us all together, about 570 people in total – men, women and children, then ordered everyone to lie down on the ground. After this, the prisoners were taken in groups of 20 to 30 to the forest pits, where they were killed and the bodies thrown into the pits. I and my children were in the last group of 32, and my husband was also in this group. We had to lie on the ground until evening, when our turn came. We were ordered to rise from the ground and put our hands on our heads, and the men were ordered to pull their trousers down to their knees. This was done to make escape more difficult if anyone tried. Thus, we were led to a huge pit, almost filled to the brim with the corpses of those killed before us. As we were led to the pit, the guards accompanying us brutally beat the men with rifle butts, sticks, and feet. To prevent my husband from running, a guard shot him in the head with a rifle butt and bruised his side. As we were being led away, I said to my husband, "Let's run. It's better to be shot in the back than to watch them shoot." My husband, badly beaten, couldn't run, so I said, "Run alone with the children." When we were brought to the pit and the Germans opened fire on us, a loud scream arose from the women and children, who were running from side to side, seeking safety. I took advantage of this, grabbed my children by the hands—a 13-year-old daughter and an 8-year-old son—and ran off into the woods. The children didn't want to run and, shouting, "We're going to daddy," broke free and ran back. I, however, continued running into the woods, as it was already dark. The Germans didn't run into the woods, but opened fire on me and wounded me in the right side. I hid in the forest for one night, and then went to the village of Maleshev, where I hid with a peasant for seven days until my wound healed, and then went to the village of Olekhnya, where I hid with an acquaintance until the arrival of the Red Army. What happened to my husband and children, I don’t know anything. I assume they were killed.

Question: Was there any other camp in Treblinka besides the work camp?

Answer: Two kilometers from the labor camp there was another camp, a "death camp," as it was called, but I don't know what it was like, since I wasn't anywhere near it and no one was allowed there. From what the guards told me, many Jews were brought to that camp and burned in special ovens. The screams of people from the "death camp" could be heard in our camp day and night.

From about August 1942, large fires burned in the "death camp" every day, day and night. The flames were visible from far away, columns of black smoke rose above the camp, and the smell of burnt flesh made it difficult to breathe. From the guards' conversations, we knew that they were burning the corpses of murdered people—Jews. This burning continued for over a year. I know nothing else about this camp.

I can't show anything else; the report has been written down and translated correctly from my words and read to me [signature/].

Translated from Polish to Russian [signature/]

Interrogated by:

Military Investigator

Guards Senior Lieutenant of Justice [signature/]

Interrogation protocol of Tanhum Grinberg on the functioning of the Treblinka death camp and the preparation of the uprising on August 2, 1943 [Błonie town] September 21, 1944

On September 21, 1944, the military investigator of the military prosecutor's office of the 65th Army, Guards Senior Lieutenant of Justice Malov, in compliance with Articles 162-168 of the Criminal Procedure Code of the RSFSR, interrogated as a witness:

- Last name, first name, patronymic: Grinberg Tanhum Haskelevich

- Year of birth: 1909

- Place of birth: Błonie, Błonski County, Warsaw Voivodeship

- Nationality: Jewish

- Social status: craftsman, shoemaker

- Education: 7th grade

- Place of residence: Błonie, Błonski Powiat

The interrogation was conducted through a Hebrew-Polish interpreter. The interpreter was Wolf Szejnberg, a resident of Warsaw.

I have been warned of liability for false translation under Article 25 of the Criminal Code. /signature/.

I have been warned of liability for giving false testimony under Article 25 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR. /signature/.

Until February 1941, I lived in the town of Błonie. In early 1941, the Germans began deporting all the Jews to Warsaw, where a special section of Warsaw was set aside for them, fenced off and isolated from the rest of the city. On February 7, 1941, I, along with other Jews from Błonie, was brought to Warsaw, where I was settled in the area set aside for Jews, which was called the "ghetto." Living conditions in this "ghetto" were terrible: they forced people to work very hard, and gave them nothing to eat. For example, for a whole day of work at the factory of the German Schultz, they gave only 50 grams of bread. The factory made shoes and clothing for the troops. There was a terrible famine among the Jews, from which dozens of people died daily, and every day, on my way to work, I saw many corpses of Jews who had died of starvation near houses. During the day, the corpses were removed. And this happened every day. In total, over 600,000 Jews from various parts of Poland lived in the Warsaw ghetto. At the end of July 1942, we were told that all Jews would be resettled to Ukraine, where they would have work and live well. And after that, Jews began to be deported from Warsaw every day. They deported 10,000-15,000, and sometimes even 20,000 people daily. On August 4, 1942, German soldiers cordoned off the neighborhood where I lived, and we were all told that today we would be taken to Ukraine, and were told to take with us the necessary things, but not more than 25 kg in weight. After that, all the men, women, and children were led to the station, where they began to load us into train cars. Our train consisted of about 40 train cars, each crammed with up to 170 men, women, and children. Given the sheer number of people, it was impossible to even sit down. People were suffocating from the lack of air and the stifling heat. We left Warsaw in the evening and traveled all night, arriving at Treblinka station in the morning. No one was allowed to leave the train cars during the journey. No one was given anything to drink, and when people asked for water, the guards accompanying the train demanded valuables. People would give up everything they had to get a sip of water, handing over money, gold, and other valuables that the guards took, but they were not given any water in return. We arrived in Treblinka on the morning of August 5, 1942. When the train entered the area surrounded by barbed wire up to 3 meters high, the train doors opened and we were ordered out. We were given only five minutes to unload. As soon as we exited the train, the guards standing near the cars began beating everyone with whips. When all the cars were unloaded, one German ordered all the men to move to the right onto the platform, and the women and children to the left, toward the barracks. Guards, or "wachmans," stood around us. After this, they ordered all the artisans and specialists to raise their hands. I, as a shoemaker, also raised my hand. And then, 204 of us out of the 6,000 people who arrived on this train, were taken aside and given some of the food confiscated from the arriving people to eat. The rest of the people were ordered to undress, told they were now going to the bathhouse. They piled all their belongings in one pile, and asked to deposit money and valuables in the cash register "for safekeeping." After this, everyone was herded toward a building they called the bathhouse. As I later learned, this was the house where all the new arrivals were gassed. When the new arrivals were herded into the "bathhouse," 204 of us were led to another part of the camp, from where the "bathhouse" was invisible, as it was surrounded by barbed wire and camouflaged by tree branches. The only sounds we could hear were the screams and cries of women and children, whom the guards were beating along the way. We, the workers, were housed in a barracks with nothing but three-tiered bunks, and we had to sleep on bare boards. The next day at 5 a.m., we were awakened and put to work sorting the belongings confiscated from the new arrivals. Between 400 and 600 of us worked on this job, depending on the amount of supplies received. The daily routine for the work crew was as follows: we rose at 6:00 AM, weren't allowed to wash, and were herded into the kitchen, where we were given one liter of coffee without bread. The coffee was simply colored dirty water, then we were marched to work. At 12:00 PM, there was a lunch break, during which we were given a liter of soup made from dirty, unpeeled potatoes. Rarely, we were given the meat of dead horses, which peasants from surrounding villages had taken out to the fields. These horses were then picked up, already decomposing, and brought back to the camp, where they were fed to us. They didn't give us bread for lunch either, as we only got bread for dinner. Our job was sorting and packing things. The work was very hard, as trains with people arrived frequently and there was a huge amount of stuff. We were guarded by Ukrainian guards, who stood around us at a distance of about five meters from each other. Each guard had a rifle and a whip. The treatment of the workers was brutal. They beat them without provocation; for example, if a person got tired during work and straightened his back, the guards would immediately beat him with whips, beat him until he lost consciousness, and very often beat him to death. I remember an incident when a Jewish man joined our team, arriving with his wife on the train. When he refused to work after learning that his wife would be killed, they didn't kill him right away, but instead beat him with shovels for two days, intermittently, until he was reduced to a shapeless mass. All this was done in front of the workers.

Another time, a Jew arrived at the camp with his wife and children. The wife and children were sent to the "bathhouse" (a gas chamber), and the Jew was sent to our work detachment. When this Jew learned what a "bathhouse" was and that his family had been murdered, he somehow stabbed one of the guards with a knife he had hidden on his person. For this, he was also beaten for two days until he died. Simultaneously, for the Jew's murder of the guard, 150 Jews were selected from the work detachment and immediately killed in the most brutal manner: whipped, beaten to death with shovels, and slaughtered with blows to the head and other parts of the body. Then, in May 1943, [while] throwing bad things into the pit, [illegible] gold was thrown in there, which the guards noticed, so they gathered all the workers in the square, including two Jews who were carrying things to the pit, brought them to the center and began to beat them with whips and shovels, and then hung them by their feet on poles specially dug into the square for this purpose. They hung like that for a long time, and then the SS-man Mitte shot them.[19] Mitte was known for his particular cruelty and hanged many people. I myself was whipped about 20 times and each time I received 25 lashes. Why they beat me, I don’t even know. Several times they beat me because, while working, in a half-bent position all day, I got tired and straightened my back for a second. Due to the backbreaking workload and poor nutrition, the workers quickly became exhausted. As soon as a supervisor saw a worker performing poorly or simply disliking him, such prisoners were sent to the "infirmary," where they were given no assistance and were immediately killed. This was most often the work of the SS officer Mitte. Up to 100-150 people were killed in this manner daily, thus the work crew was replenished daily by new arrivals. I spent five months on the team sorting the belongings of the exterminated Jews, and then, as a shoemaker, I was transferred to the shoe shop, which was located in the same barracks where the work crew lived.

In the shoemaker's workshop, we made shoes for the German army. The material we used was shoes confiscated from Jews, Poles, Czechs, Roma, and others exterminated in the camp. There were 24 shoemakers working in the workshop, and we made up to 15 pairs of shoes a day. I worked as a shoemaker until August 1943, that is, until the Jewish uprising. As a result of the uprising, many, including myself, fled the camp.

Next, I want to talk about the preparation and execution of the uprising in the "death camp," or Camp No. 2.

While in the camp, despite the strict security and the near impossibility of escape, many considered fleeing the camp and would rather be killed than endure terrible hardships and expect a painful death any day. Gradually, a group of six or seven people formed in the camp who decided to develop an escape plan. This group included the Jews Kurland[20] and Raizman, who now lives in the city of Węgrów, the Jews Mardins, Dr. Rybak,[21] and Dr. Raizman.[22] I don't know the names of the others. Engineer Galewski was also an organizer. The whereabouts of the others, besides Raizman, I don't know. These people prepared the escape plan. Almost all the camp workers knew about the uprising. To carry out the escape, weapons were needed. To this end, while sorting things, we used various means to pass hidden money and valuables to the camp doctor, the renowned Warsaw professor Horonzhinsky, who used them to buy and give us eight pistols. In May 1943, SS men discovered money on Khoronzhinsky and began to question him about where he got it. Since Khoronzhinsky did not say this and did not reveal the conspiracy, the SS killed him. Preparations for the uprising lasted about four months. One of the prisoners had access to the gun shop, found the key, and on August 2nd, the day the uprising was scheduled, opened the shop and we took about 80 grenades, most without fuses, and several submachine guns. The uprising began at 3:30 PM on the signal—a gunshot. Since [the] tasks had been assigned in advance, the camp guards were quickly disarmed. At the moment of the signal, a grenade was thrown into the gasoline tanks, which started a large fire and set the barracks ablaze, increasing the panic even more. Taking advantage of this, some 80 people, some of whom escaped from the camp through gates and passages cut in the barbed wire fences, were able to escape. Gendarmes from neighboring villages immediately launched a roundup, and many of the escapees were caught and killed. Many others, unable to escape, were murdered in the camp. After the prisoners' escape from the "death camp," the Germans,[23] fearing publicity and exposure of the unprecedented crimes they had committed in the camp, began liquidating the "death camp." No more trains arrived at the camp, but for about a month, an oven burned in the camp, where the remaining corpses were incinerated. Afterward, all the ashes were mixed with the earth, and the camp grounds were then sown with lupine and other crops. All the ovens and barracks, with the exception of one, were completely destroyed, so it is now difficult to recognize that this site once housed a gigantic extermination factory where several million people, mostly Jews, were murdered.

Question: Tell us what you know about the mass extermination of people at the Treblinka "death camp"?

Answer: From August 5, 1942, when I arrived at the "death camp," until August 1944, I witnessed two to four trains of up to 70-80 cars, and sometimes even more, arriving at the camp daily.[24] The trains were primarily carrying Jews from Poland, as well as from other German-occupied countries: France, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and others. Each train contained approximately 170 men, women, and children. The arriving train entered the "death camp" grounds, where everyone was ordered to quickly exit the cars. Since the entire train could not fit into the camp, about 20 cars would enter, from which people were unloaded, and then the train would continue on, unloading people from the next 20 cars. And when the entire train was unloaded, the carriages were swept, and the empty train left the camp grounds.

The guards who escorted the train to the camp were not allowed onto the camp grounds, as everything that happened in the death camp was kept strictly secret, and no one who entered the camp ever left. During unloading, the entire train was surrounded by guards to prevent escape. When unloading was complete, the command was given: men to the right, into the square, and women with children to the left, into the barracks. After this, everyone was ordered to strip naked, saying they were going to the bathhouse. After this, all the laundry was thrown into a pile. In the barracks where the women undressed, there were several Jewish hairdressers who cut the women's hair, which was then sent to Germany for some unknown purpose. Before this, everyone was told to take all their money and valuables with them and deposit them in the cash register "for safekeeping." People, unaware of what awaited them, believed it, as they were told they were being taken to Ukraine and handed over valuables. While the SS men were undressing, Unterscharführer Sukhomel hurried them, saying that the water would cool down in the bathhouse, but also that soap and towels would be provided there. Once the men had undressed, a group of five to six thousand was herded from the changing rooms down the corridor to the "bathhouse." While the guards were urging the men on, they beat them with whips, but when they were herded into the "bathhouse," the real atrocities began. Along the wire-fenced corridor leading to the bathhouse, Ukrainian guards stood with whips in hand, mercilessly beating women, children, and men passing by. At that moment, the incessant screams and cries of women and children echoed throughout the camp. Driven mad by fear and pain, they ran to the "bathhouse," unaware of what awaited them there. The sick and elderly, unable to move, were carried on stretchers to the "hospital," which consisted of a small building surrounded by barbed wire and camouflaged so that the interior could not be seen from the outside. A sign above the entrance read "Hospital." In the "hospital" were an SS soldier and a Czech named Bakhmanov,[25] who was dressed in a robe and had a red cross on his armband. Near the building was a large pit. When a patient was brought to the "hospital," they would sit him on a chair near the pit, and SS men or Bakhmanov would shoot him in the back of the head from behind, after which the body would be thrown into the pit. I witnessed all of this myself when I was brought to the death camp. Furthermore, while later working sorting things, I had to visit the "locker room" and the "hospital" several times, so I witnessed all of this. I didn't see the extermination of people in the "bathhouse" gas chamber, but from the accounts of a Jew named Abram Golberg, who worked carrying corpses from the "bathhouse" to the pits and ovens, and from the accounts of one guard who released gas into the "bathhouse," a man named Ivan the Ukrainian, I know that the bathhouse was a building with a corridor running down the middle, with rooms on either side of the corridor, each measuring approximately 5 x 5 x 2.5 meters, with cement walls and floors. I don't know how many cells there were, but the entire building was about 20-25 meters long. Each cell had a metal spout in the ceiling, reminiscent of a shower. The floors of the cells were doused with water, so that those trapped there would have the impression they were actually in a bathhouse.

Each cell had a large door facing the outside of the building. All doors were hermetically sealed and locked from the outside. Each cell could accommodate approximately 450 people. Between 5,000 and 6,000 people were forced into the "bathhouse" at a time, so cramped that they couldn't move a muscle, arm or leg and suffocated from the cramped conditions. Afterward, all the doors were locked, and Guard Ivan would start a motor parked outside a few meters from the bathhouse. A pipe ran from the motor to the bathhouse and then spread throughout all the cells. The motor resembled a tractor. I don't know how the suffocation occurred, but the Jew Golberg said that when the motor was turned on, it first pumped the air out of the cells, and then released exhaust gases from the motor into the cells. How this all happened, I don't know. The motor ran for 15-20 minutes, and that was enough to kill everyone in the cells. After this, all the outer doors were opened, and the corpses were dragged outside, where they were laid face up on the ground before being thrown into the pits. Several Jews, holding pliers, walked around, looking for gold teeth, and then extracting them. After all this, the corpses were thrown into the pits, and later directly into the ovens. Up to 15,000 to 18,000 people were killed in this way daily. There were cases when up to 22,000 people were killed in a single day. According to rough estimates, at least 3.5 million people were strangled during the existence of the "death camp." This can be judged by the amount of clothing confiscated from the prisoners. All clothing was sorted and packed into bales: coats of 10, jackets of 10, trousers of 25. All this was loaded onto train cars. A train car held 4,500 coats, 10,000 trousers, 45,000 pairs of shoes, and almost every week 60 to 120 train cars loaded with things were sent to Germany.[26] When I arrived at the camp, there were only three asphyxiation chambers. Then, at the end of 1942, they began to build new ones, but I don’t know how many there were in total. From the beginning of the camp’s operation, that is, from July 1942, the bodies of people strangled in gas chambers were carried to enormous pits, where they were placed by the tens of thousands and covered with earth. At the end of 1942, dredging machines were brought to the camp, which dug up to 8 enormous pits measuring 50x50 meters and 8 meters deep. Concrete pillars were dug into the bottom of the pits, on which rail gratings were laid. Then they dug up the old graves and, using the same excavating machines, began to drag the bodies into these pits, which could hold up to 20,000 corpses each. Once the pits were filled to the brim, they doused the corpses with flammable material and set them alight. This was how the corpses were destroyed. This burning of the corpses lasted for many months. During this time, columns of black smoke rose above the camp, the fires were visible for tens of kilometers, and the unbearable smell of burning flesh permeated the surrounding area. At this time, and subsequently, the corpses of the strangled people were no longer buried but thrown directly into the ovens and burned. At first, fuel was used for kindling, but then an SS man who arrived from Lublin reported that women burned very well. From then on, the ovens were heated with the corpses of women, first cutting the corpses into four pieces. The legs burned especially well.

Question: What nationalities were the people primarily exterminated in the "death camp"?

Answer: The Treblinka death camp primarily exterminated Jews, who were brought there from all over Poland and other German-occupied countries: France, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Germany itself. Several trains of Roma were brought, and shortly before the "death camp" was destroyed, two trains of approximately 60 train cars of Poles were brought in, who were also exterminated.[27] But, as I already said, the camp's primary extermination population was the Jewish population.

Question: What was the ashes from the burning of corpses used for?

Answer: The ashes remained in the ovens, and after a certain period of time, a layer of sand was poured over them, and then the ovens were relit. Very little ash was produced after the burning of the corpses.

Question: What were the roads in the camp and the highway covered with?

Answer: The roads in the camp and the highway were covered with coke and slag, brought in specifically for this purpose. Ashes from corpses were not sprinkled on the roads.[28]

Question: Who do you know of those who committed murder in the camp?

Answer:

- The camp commandant, Hauptsturmführer Himala, was a German from Poznan, about 45 years old, of average height, healthy, blond, and rarely visited the camp, only to check on the situation.

- Untersturmführer Franz – deputy commander of the "death camp," a German, worked as a cook before the war, tall, with dark hair and black eyes. He was known for his exceptional cruelty in his treatment of prisoners. He personally participated in beatings and executions. He always carried a rifle and practiced his marksmanship by shooting at people. He personally punished people with whips, always carrying a large dog, pointing it at people, and amused himself by watching the dog tear out chunks of flesh.

- Untersturmführer Mitte – German, 25 years old, of average height, walked with his head to one side, and had one gold tooth in his upper jaw on the right side. He was also known for his exceptional cruelty. He personally hanged dozens and shot hundreds of people from the labor detachment.

- Unterscharführer Sepp – a German, a former criminal killer, 35 years old, tall, healthy, chubby, black. His cruelty went so far as to take two-month-old children, step on one leg, and, pulling the other, tear the children in half.

- Unterscharführer Mille[29] – a German from America, did not commit murders himself, but rather was a denunciator. It was on his denunciation that the famous Warsaw doctor, Professor Choronzhinsky, and many other Jews were killed.

- Oberscharführer Ludwig[30] – a German, engaged in the beating of Jews and the rape of women.

- Unterscharführer Paul[31] – a German, 27 years old, short, black, with a mustache, of strong build. Like Franz, he was distinguished by exceptional cruelty, personally beating and shooting Jews.

- Unterscharführer Sukhomil – a German, 32 years old, blond, of medium height, supervised the unloading of train cars and beat people while herding them into the "bathhouse."

- Unterscharführer Bals – a German, thin, short, with a fair complexion, surpassed Franz in his cruelty. As soon as a train arrived, he was the first to approach it and begin beating them with a whip, escorting them all the way to the gas chamber. He beat dozens of people to death.

- Wachmann Widzemann – a Russian German, tall, fair-haired, demonstrated exceptional cruelty, was the senior guard of the "death camp," beating not only Jews but also guards, and brutally beating Jews with whips.

- Tsugvakhman Rogoza, Ukrainian, 22-23 years old, blond, healthy, demonstrated exceptional cruelty when beating Jews, herding them into the gas chamber. He beat dozens of people to death.

- Tsugvakhman Loch, German from Russia, 30 years old, short, blond. He stationed guards and personally beat Jews with whips.

- Tsugvakhman Videnko, Ukrainian, 25 years old.

All of these individuals were exceptionally cruel. They beat, shot, hanged, raped women, and took an active part in the extermination of Jews.

I would like to add that construction of the death camp began in March 1942; it lasted four months, and in July 1942, the first trainload of Jews from Warsaw arrived. The camp was built according to the designs of SS architect Schulte.

I can't show you anything else. The report has been written down and translated correctly from my words and read to me: /signature/.

Translated from Hebrew to Russian: /signature/

Interrogated by: Military Investigator, Guard Senior Lieutenant of Justice /signature/

Interrogation protocol of Genia Marciniakówna regarding the construction and operation of the Treblinka death camp. Village of Kosów Lacki, September 21, 1944.

Kosów, September 21, 1944.

Senior Lieutenant of Justice Yurovsky, military investigator of the 65th Army's Military Prosecutor's Office, interrogated the following as a witness, who testified:

Marciniakówna Genia, born in 1925, native of Rakoświca, Wołycin County, Poznań Voivodeship, Polish, resident of the Grabnia prison colony in Kosów.

Having been warned of liability for retracting testimony and for giving false testimony, she stated the following:

Question: How did you come to work at the Treblinka camp?[32]

Answer: In January 1942, due to the illness of my friend Roza Shlaynova, who worked as a cleaner in the gendarmerie, I temporarily took her place and worked there for two months—until she recovered. Around March, I left this job. According to the procedure in force at the time, employers were required to notify the labor exchange when laying off an employee. This was the case with me. The gendarmerie duly notified the labor exchange of my dismissal, which registered me as unemployed. In late May 1942, my friend Zosya Mitovskaya invited me to the house of my friend Kalyata.

When I entered Kalyata's apartment, Mitovskaya, Kalyata, and an SS Obersturmführer, a German named Lampert and first name Erwin, were already there.

Zosya Mitovskaya, knowing I was unemployed, offered, in Lampert's presence, to go with her to work in Treblinka.

Lambert intervened in our conversation. He told me he needed two women to work as cooks at Treblinka. The salary, we learned from him, was 250 zlotys per month. The only thing he told us was that we'd have to travel to Treblinka station and the salary was 350 zlotys per month. Not a word was said about the camp. Mitovskaya and I agreed.

I must admit quite frankly that I was not particularly picky in choosing a place of work for the simple reason that I needed to find a job close to Kosów as quickly as possible, since otherwise I would undoubtedly have been sent to Germany. Moreover, the labor exchange had once intended to send me to Germany, but this time I managed to avoid this fate. The day after my first meeting with Lambert, he arrived by car in Kosów and took me to Treblinka.[33] This was May 28, 1942. We drove to the forest 3 kilometers from the village of Wólka Okrąglik. At that time, there was one small barracks in the forest. A second, much larger one, was being built. By the time of my arrival, approximately 50 Poles and 150 Jews were busy building the barracks and cutting down trees. On the third day, another 150 Jews were brought from Węgrów. And then the hasty construction of a barbed wire fence began. Only then did I learn that I was on camp grounds. It's worth noting that the Germans didn't say anything about it. I learned about the camp's establishment from a Jew, who told me that people would be brought there for various types of labor.

Camp No. 2 subsequently became a kind of death factory.

Approximately two or three kilometers away from this camp was Camp No. 1, where primarily the Polish population was transported. I can't say anything at all about that camp because I didn't have access to it.

One small barrack, as I've already shown, contained a kitchen and dining room for the Germans, the camp office, and two living rooms. The commandant lived in one, and Mitovskaya and I in the other. The barrack also had an annex where five Germans from the camp staff lived. The remaining Germans, about 25 in total, stayed on the camp grounds during the day and went to Camp No. 1 to sleep in the evening. That's how it was for the first week of my stay in the camp. Then they built two more large barracks and a barn with a sand floor. The Germans lived in one barrack, and the Ukrainian guards in the other. All the Jewish workers slept in the barn, right on the sand, because there was practically no floor. Fifty Polish workers were allowed to go home at night. All of them were residents of nearby villages. The camp's construction lasted two months. Most of the workers were Jews. In addition to the three hundred Jews I mentioned earlier, up to three hundred Jews from Warsaw and Węgrów were brought to the camp by car during these two months. All of them were used for various construction jobs in the camp. For the first two months of the construction period, two Germans dressed in civilian clothes oversaw the overall construction. Then, after a month, they left, and command of the camp's construction passed to Obersturmführer Erwin Lampert.

The camp was built in the following order. After the first, so to speak, phase of the camp was completed—the barracks for the dining hall and office, the barracks for the Germans, the barracks for the Ukrainian guards, the food warehouse, and the barn for the Jewish workers—this entire section of the camp was hastily surrounded by a barbed wire fence up to three meters high. Moreover, the bare wire mesh was heavily interwoven with pine branches. Under these conditions, the fence appeared to be a continuous canopy of vegetation. So from a distance, it was impossible to even see the wire itself. Moreover, the spruce branches intertwined so densely that absolutely nothing could be seen on the other side of the fence. Once, before the fence was finally erected, I witnessed the construction of several barracks in another part of the camp, where the extermination of a huge Jewish population would later take place. I remember one of the Poles working on the camp's construction telling me that a large stone house was being built in the camp, its rooms upholstered in red cloth. He didn't tell me anything about the building's purpose. A railway line had been built to the camp. It ran behind the fence along the first part of the camp, where the camp staff were housed, and entered the other, main part of the camp grounds. I know no other details about the structures erected within the camp. Everything that was being built there, everything that happened—the Germans and the Ukrainian guards kept all of this a closely guarded secret from us. I was never able to visit that section of the camp where large numbers of people were later sent.

Now about the regimen of the Jewish construction workers during the camp's construction.

All of them, up to 300 of them, slept in barracks on the bare ground and rose for work at 5:00 a.m. Work continued until 12:00 p.m., then, after a half-hour break, until 6:00 or 7:00 p.m.

For the entire day of grueling labor, they received only one cup of coffee without milk each morning, soup (unpeeled potatoes boiled in water) for lunch, and whatever was left over from dinner in the evening. They received up to 200 grams of bread per day. Starving after the grueling, heavy labor, the men would violently push each other aside and, like madmen, rush into the dining room, eager for a better portion. Right there, the commandant and other Germans who had arrived by this time would beat the Jewish workers with whatever they could lay their hands on. I recall one incident when the commandant, in an attempt to "restore order," as they always explained their abuses, grabbed a large board lying near the kitchen and beat the Jews crowding around it with such force that the board shattered into pieces.

A Jew from Węgrów—I don't know his last name—a boy of about 17, dark-haired and clearly showing signs of exhaustion, couldn't bear the beating and fell unconscious. The commandant—I don't remember his last name because he was only in the camp for two construction months, June and July—stood by his side until he regained consciousness.[34] And in front of everyone, as a form of "punishment," he ordered the exhausted young man to climb down a well to retrieve a bucket someone had lowered into it. The young man descended and fell to his death. With difficulty, they pulled him out, and as a "guilty" worker, by order of the commandant, he was taken to the forest and shot. Backbreaking labor, hunger, beatings, the most brutal insults, and the constant execution of those emaciated and unfit for labor—such was the regime, such was the working environment for Jewish workers during the camp's construction. The Germans insulted the national feelings of the Jews at every step they could.

They beat them with clubs for no apparent reason. They used any hard object, usually pine sticks, as clubs. Leather whips were widely used. A whip was an indispensable attribute of every German. The Germans shot all those who lost their last strength in the camp and were unable to continue working. At the end of June 1942, I personally witnessed the Germans taking about 100 Jews who had become incapacitated into the forest for execution. This group of Jews was escorted from the camp by up to 20 Germans and Ukrainian guards. All of them were armed with carbines. Each Jew carried a shovel. About an hour later, we heard three volleys of gunfire from the forest. An hour later, the Germans and Ukrainians returned from the forest. They were carrying shovels. Not a single Jew returned.

By the end of July, it was clear that construction of the main camp section was complete. The entire camp was surrounded by a barbed wire fence woven with pine branches.

A railway line was built right into the camp grounds. With the completion of the camp's construction, a change of commandant took place: Dr. Franz Ebert was appointed camp commandant. Along with him came Staff Sergeant Stady, deputy commandant; Untersturmführer Mecink, senior in the office; and Untersturmführer Schmidt, a driver. A little later, about a month later, Franz Kurt arrived as assistant camp commander, or, what was the same thing, commandant; Oberscharführer Sepp Post; and Untersturmführer August Mintzberger. From the end of July, a continuous stream of trains carrying the Jewish population began to arrive at the camp. The trains traveled along the fence near the section of the camp where the service personnel were housed and then entered the main camp grounds. I didn't see what was there. However, it was clearly visible how, almost every hour, a train of 10 to 15 cars, completely packed with Jews, approached the camp. The cars were closed. Small windows were left for air, and from behind the iron bars, distraught faces peered out.

Terrible, incessant screams emanated from the train cars. From the gestures of these people, it was clear they were asking what kind of death awaited them: firing squad or hanging.

A Jewish woman from Warsaw named Chesia later told me that the train from Warsaw to the camp took three days. Each car held about 250 people.[35] There was no room to lie down, not even sit down. They weren't given any water for three days. They relieved themselves there, in the car. Children died. One dead child had to be thrown out of the moving car with special permission from the Germans. Chesia, driven by the lack of water, became so frantic that she gnawed through a blood vessel and drank her own blood. As I've already shown, for the first month, trains of 10-15 cars moved in an endless stream, replacing each other every hour. Subsequently, trains arrived regularly, but much less frequently—two or three per day.

The camp was where the Jewish population was transported from various countries of occupied Europe. I personally encountered Jews from Germany proper, as well as from Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Austria, Russia, Greece, and Belgium. It's important to note that a significant number of Jewish intellectuals were brought to the camp. For example, the famous Polish composer Gold Fock was held in the camp. I personally, quite by chance, had the opportunity to speak with a professor from Vienna. From conversations with the Jews themselves, I learned that some of them were brought from Bulgaria, some from Belgium, and some from Russia—the part of Russia that was then occupied. Some time after the camp began operating, its purpose as a kind of factory for the mass extermination of the Jewish population of all of occupied Europe became clear to me. Every day, during my entire year there, two, three, or four trains with train cars crammed with Jews arrived at the camp. Entire families were brought in. Among them were men and women, children and the elderly. No one left the camp. The smell of corpses and burning human flesh hung over the camp constantly. Clouds of smoke filled the sky almost daily. There was almost no fresh air in the camp area. The stench of corpses poisoned the air day and night. It was clear to everyone that people were being burned on these pyres. I wasn't in the main camp area, where this mass extermination of hundreds of thousands of people took place. But from the stories of individual Jews who were temporarily assigned to various jobs, I learned of this horrific, savage picture of human extermination. Two girls from Warsaw named Pola and Bronya told me the following: as soon as the train stopped at the camp grounds, the cars were immediately opened and everyone was asked to form a line. They were told that all personal belongings, including money and gold, were to be handed over for safekeeping. They were to keep one towel and prepare for the bathhouse. All the Jews complied with this order and formed a long line for the bathhouse. The Germans selected some young, attractive girls from this line and took them to the part of the camp where the camp staff offices were located. They were among these "chosen ones." When they asked a German why their mother hadn't been taken with them, he replied that she would return after the bathhouse. The girls never saw their mother again. In December 1942, I fell ill and was absent from the camp for two months. When I returned, I was immediately struck by the significant expansion of the camp's territory.

Not to mention that each of the many thousands of people who arrived at the camp lost their lives within a certain, often insignificant, time. During the limited time they were able to survive, they were subjected to a whole system of the most savage abuses. This began with the Germans, upon the arrival of each group, stopping at nothing to rob the Jews, taking all their personal belongings, money, and gold jewelry under various pretexts. Then, those who were immediately sent into this diabolical death machine suffered the most exquisite abuses.

The latrine window in the part of the camp where I was located looked directly onto the part of the camp where the Jewish barracks were located. It was one day in the spring of 1943. I heard screams and groans coming from the latrine next to these barracks. Looking out the window, I saw this: Untersturmführer Post and two Ukrainians were beating a middle-aged Jew with sticks and whips. The man was lying on a wooden couch, screaming and groaning after each blow. Post and the Ukrainians were relentlessly and savagely beating him all over his body, his head, his face. Blood began to flow from his mouth, nose, and ears. This didn't stop the executioners. They beat him until he died.

Camp Commandant Dr. Ebert repeatedly beat Jews with a whip before my eyes. He often drank, and his favorite spectacle then was watching young Jewish women dance under force. He would then erupt into a terrifying laugh, shout insultingly at them, and fire aimlessly from his pistol. Deputy Commandant Stadi had his own methodical beating procedure, devised by himself. He would summon everyone who had "offended" in any way during the day and, along with other Germans, beat them with whips. Jews from the all-work detachment repeatedly told me about this. Franz Kurt arrived at the camp around September or October 1942. He always acted as a substitute for the commandant when he was away, despite not having an officer's rank. By the spring of 1943, he had risen to the rank of officer and in May was appointed commandant.[36] Kurt was known for his ferocity. His room was in the same barracks where I lived. He often brought Jews to his room and beat them. He always loved to walk with his bulldog. This dog was specially trained: whenever he started beating a Jew, the dog would immediately pounce and bite. Groans and screams were often heard coming from Kurt's room. That's all I could tell you about them—the Germans who ran the camp. It must be kept in mind, however, that I had no access to the part of the camp where the Germans' main professional activity took place—the murder of thousands of people. All the Germans serving in the camp belonged to the SS. Representatives of the highest fascist command visited the camp on numerous occasions. In the summer of 1943, a general came, reportedly from Lublin. Someone came and went from Berlin every two weeks, each time taking a large iron box. It seems to me that the contents were nothing but gold.

On August 3, 1943, the Jews held in the camp revolted.[37] At 4:00 PM, while in the kitchen, I heard gunfire coming from the main camp area. The sporadic shooting grew louder. Confusion broke out in the camp. I ran out of the barracks with the Ukrainians and rushed for the exit, but the guards blocked my path. Before my eyes, some Jews still managed to escape. The Germans and the guards brutally shot all the Jews in the camp at the time. Those who were not fatally wounded were finished off by the guards with an axe blow to the head. Thus, from what I could see, at least five Jews were killed. The revolt was suppressed. Most of the Jews were shot. The rest were taken to the Lublin camp.[38] It should be noted that immediately after the revolt in August, I was dismissed from my job at the camp. The last batch of Jews was sent to Lublin in November. Therefore, I can’t say anything about what happened after I left the camp.

Question: What conversation did you have and what signature did you give when you began working at the camp?

Answer: In late June or early July 1942, that is, after a month spent in Treblinka Camp No. 2, I was summoned to the camp office by Unterscharführer Metzink. Commandant Dr. Ebert, Staff Sergeant Stady, Metzink, and Zosia Mitovskaya were in the office when I arrived. As soon as I entered, Mitovskaya called me in and told me I had to sign a secrecy agreement. I asked Mitovskaya to read me the printed text of the agreement. She spoke German fluently and read it to me. The literal content of the agreement obligated me to maintain the secrecy of everything I had seen or known about the camp. Standing there, Ebert, Metzink, and Stadi verbally repeated the warning about maintaining the secret and the risk of their lives if they disclosed it. I signed a written agreement.

I have nothing more to add. This is written down accurately from my words and was read to me [signature/].

Military investigator of the Military Prosecutor's Office of the 65th Army, Senior Lieutenant of Justice [signature/]

Interrogation protocol of Abram Goldfarb, who worked on the team transporting corpses from the Treblinka gas chambers. Village of Kosów Lacki, September 21, 1944.

The city of Kosów, September 21, 1944. Senior Lieutenant of Justice Yurovsky, military investigator of the 65th Army's Military Prosecutor's Office, interrogated the following witness, who testified:

Abram Isaakovich Goldfarb, born in 1909, native of Szczuczyn, Szczuczyn County, Białystok Voivodeship, resident of Szczuczyn, Jewish, shoemaker.

Having been warned of liability for retracting testimony and for giving false testimony, he stated the following:

My permanent place of residence was the city of Szczuczyn, Białystok Voivodeship.

On September 7, 1939, German troops occupied my village, and on September 9, I was sent to a prisoner-of-war camp—the village of Terpen, Belev district, East Prussia. I remained there until November 1940, when I was transferred to the Bela Podlaskie camp for civilian Jews.

I spent only two weeks in this camp and was released due to illness. Unable to reach my family, I remained in Mięziżec Podlaski until August 17, 1942.[39] On the night of August 17–18, I was awakened by the sound of random rifle and machine gun fire in the streets. This continued until the morning. I was completely unaware of what was happening in the city. Early in the morning, some boys ran from the yard and reported that the Germans were evicting the Jewish population from the city. Many different rumors were circulating: some said they would be taken to Ukraine, others – deep into Poland, and so on. At 7 a.m., a policeman, an ethnic Ukrainian, came to my apartment and ordered me to grab the necessary things and go to the city square.

By the time I arrived, about 18,000 Jews had already gathered in the square. The Germans selected 4,000 specialists from this mass and allowed them to remain in the city, while the rest of us were marched to the train station square. Many were missing when we boarded the train. In the city square, as well as along the way to the train station, the German gendarmes shot anyone for the slightest sign of fatigue or physical illness. Up to 300 people, mostly elderly, were executed in this way. On Lyublinskaya Street, we witnessed the Germans throw a small infant out of a second-story window. The German gendarmes opened fire on the parents who ran to the child. Until the very moment we boarded the train, the gendarmes—up to 400 of them, including Ukrainian police officers—beat the people marching in the column with whips for any, even the most trivial, provocation. On August 18th, a train of about 80 cars arrived. The cars were packed to capacity. Suffice it to say, there were 215 people in my car. Under these conditions, it was impossible to lie down, let alone even sit down. The doors were immediately locked from the outside as soon as we boarded the carriage. Air came in only through eight small windows, which were actually designed for birds. We left the town of Menzizhets at 11 a.m. on August 18th. We arrived at Treblinka[40] station at 5 a.m. on August 19th. We were forced to stand around the entire time. Not only were we denied food and water, but any attempt to get water was also stopped by shooting on the spot, and everyone had to relieve themselves in the same carriage. There was such an incident in our carriage. At Małkinia station, a seven-year-old boy climbed out of a carriage window. He managed to get water once, but when he tried to get it again, a German gendarme shot him. This was not an isolated incident. Many corpses could be seen on the railway tracks.

To our endless questions about our fate, the Germans accompanying us told us they were taking us to Ukraine, where a completely separate city had been set aside for Jews. This is what they told us in Medzizhets, this is what they told us at Małkinia station. From Małkinia station, a separate railway line ran to the Treblinka camp. As we approached the camp, we noticed a wooden fence, 2-3 meters high. Three rows of wire were attached to the wooden fence, at a slight angle to the fence. The Germans' diabolical plan to exterminate Jews immediately began to manifest itself. From Małkinia station, our transport consisted of not 80 cars, but 20. The remaining 60 were temporarily abandoned at Małkinia station until the first 20 cars were unloaded. And when the doors of the cars were opened at the Treblinka camp station, it turned out that 50-100 people in nine of the cars had died en route. In the remaining 11 carriages, almost everyone died of suffocation.[41] Many of the bodies, however, bore traces of gunshot wounds—the work of the gendarmes en route. In our carriage, for example, because it had eight windows (it was adapted for transporting birds), the mortality rate was relatively low—15 people, all from suffocation.

It's important to note that many of the corpses with gunshot wounds were particularly swollen and blackened in the areas where the wounds had originated. In one of the carriages, only one person remained alive—Leib Charny from Medzizhets. He was brought back to consciousness with difficulty. He recounted that after the gendarmerie fired on the carriage, not only those who had sustained any wounds died, but everyone else as well. He claimed that the poisonous gases in the bullets had this devastating effect. Once a bullet had struck a person, it caused swelling and blackening of the infected area.

Everyone was asked to go out onto the platform. Jews who had arrived before us were walking along it. There were also numerous corpses lying nearby. I'm at a loss to estimate their number, but I can say one thing: we were stunned by the whole scene.

The women, children, and elderly people were separated from us and taken away. We never saw them again. The younger men were added to a group of Jews working in the camp at the time of our arrival, and we were all given the task of dragging corpses from the train cars onto the platform. From there, they were loaded onto carts, which then took them to the field. At the time, an excavator was digging three enormous pits there. The Germans, observing our work, periodically fired at the workers from various directions, as if jokingly. After this horrific "amusement" of the Germans and Ukrainian guards, by evening only 40 of the 120 Jews working on the platform remained. The next day, we carried the corpses to the pits. Yakov Vernik,[42] later the author of the brochure "A Year in Treblinka," was also involved in this process of carrying corpses. The work of moving corpses from various locations to the pits continued for four days. After this work was completed, all the Jews held in the camp were gathered in the field at night for a roll call. This refers exclusively to men, as everyone else was taken to the bathhouse on the very first day and never returned. 980 people were gathered for [illegible]. Almost all were men. The exception were 25 young women selected by the Germans. From the total of 980, a group of 80 different specialists was selected, and then Scharführer Max Miller[43] asked everyone who spoke German. Forty responded. All of them were brought to the pits that same night and shot. The rest were given various tasks, including a significant group sorting through the personal belongings taken from the Jews who had arrived at the camp.

Max Miller, addressing the assembled Jews, constantly called on the latter to hand over all their personal belongings, money and gold for safekeeping under the pretext that they, the owners of these valuables, would have a rich future.[44]

A week after my arrival at the camp, I was assigned with 32 other prisoners to work on the construction of a building containing the cabins in which people were subsequently killed. By the time I arrived, the camp already had a building containing three cabins for killing people. The building was located in the forest, 200 meters from the Treblinka station platform. The approach to the building was protected by a barbed wire fence, into which pine branches were woven for camouflage. The building itself was an ordinary one-story brick structure with a metal roof. As you ascended the entrance staircase, you first entered a wooden annex, resembling a corridor. Both the entrance door to the building and the three iron doors leading from this annex to the three cells in the building were hermetically sealed. Each of the three cells had the following dimensions: length – 5, width – 4, height – 2 meters. The floor and walls were tiled, the ceiling was cement.

Each cell has a single hole in the ceiling, covered with mesh. A pipe with a distinctive bell-shaped mouth and a mesh bottom extends from the wall into the cell. The bell-shaped mouth is mounted almost against the wall. The wall at this point is heavily soiled with soot. Opposite the entrance door is a hermetically sealed exit door. All three doors in these cells open toward a concrete ramp installed right next to the building. This is a brief static description of this building. Since one night in mid-September, I was assigned with a group of prisoners to remove the bodies of murdered people from this building, I can say something about the method of this killing. Each of these cells was exceptionally densely packed with corpses. Both the cells themselves and the corpses reeked of the exhaust fumes from the flammable mixture. Most of the victims had copious traces of bloody discharge coming from their nasopharynxes. At first, a narrow-gauge railway was built to the building, along which we transported corpses on carts to the pits. Regarding the structure of the building and the mechanics of extermination, it's crucial to note that an ordinary tractor engine was installed in an extension to the building, which was used for two purposes: when the chambers were filled with people, and for lighting purposes. Furthermore, a single exhaust pipe from this generator, carrying exhaust gases, was run through the attic into the building to each chamber, and, as I've already shown, the gases exited through a bell in each chamber.

Another pipe from the generator exited directly to the street. This is clear: when the engine was used for killing people, gases were introduced through a system of pipes into the chambers, but when its primary purpose was to power the electrical grid, the gases exited directly to the outside.

There were two guards working at the engine.[45]